Quiet, efficient balance

This article and set of exercise were put together by Jenex, makers of roller skis, and were supplied to me by Tom Jones of Euroski. The exercises, in particular, seem to work, and it builds on the article on Ultimate Balance we had in a previous Newsletter.

To roller and snow ski with relaxed power, efficiency and confidence, you must balance quietly. Quiet balance is economical and effective and it's achieved with small, subconscious corrections that are imperceptible to the outside world. To skiers it's vital, because quiet balance lets you glide on a steady roller or snow ski which not only glides faster and further after each push but feels secure and capable of dismissing every imperfection on the road or track. It rewards you with faster times, better tours, and it sends you back to the tracks with a smile because skiing has become so much more fun.

In comparison, if your balance is noisy, more frequent, bigger corrections, you create an unsteady ski. In your search for balance and stability, you move the focus of pressure around and around, Every rock, roll and balance-saving totter transfers directly to your skis. As a result, you lose momentum and need to kick or skate earlier than if you glided on a steady ski. In addition, you focus more on balancing and less on gliding in confidence and comfort.

It doesn't matter whether you skate or ski classic, if you increase your balance skill and stabilization strength, you will balance more quietly and glide on a steady ski. Fortunately, the ability to balance quietly is not exclusive to the elite only. With surprisingly little practice, you can enjoy the many benefits of quiet balance: longer glide, better power transfer and greater energy efficiency.

Balance in two-part harmony

Quiet balance comprises two components: proprioception and stabilization. Together, they form a vital alliance, an amazing brain-to-brawn operation which, when properly tuned, liberates precision and efficiency; invaluable assets for racing and touring.

Proprioception

Proprioception is the nerve centre of quiet balance. It supplements your vision, which is essential to balance, with a continuous stream of sensory information captured throughout your body by specialized receptors called proprioceptors. These are responsible for the keen sense you have of your body's position, called kinesthetic sense. Combined, you proprioceptors faithfully check the status of your balance and create the solutions to correct any deviations which, if left unchecked, may topple you. Proprioception needs a partner, however, to implement its sophisticated schemes. That partner is muscle, muscle for stabilization, the second component of quiet balance.

Stabilization

Stabilization is the application of muscle force for support so you can sit, stand and ski with aplomb. You have two types of stabilizing muscles: primary and secondary, and both are directed by your proprioceptors.

The core muscles that support your trunk (your spinal erectors and the muscles of your abdominal wall are good examples) perform the critical task of primary stabilization. The firmer you make your trunk by strengthening these muscles (front, back and sides) the more propulsive power your arms and legs can liberate (see how this links with our article on Pilates. Don't things fit together very neatly? Ed). This is because a stronger trunk is not only a firmer anchor for your arms and legs to work against (greater efficiency), it also does more balancing, which allows your power muscles to focus on moving you, not keeping you upright. Strong primary stabilizers enable quiet balance, efficiency and power.

The muscles which stabilize and steer the joints of your arms and legs do the work of secondary stabilization. Secondary doesn't mean less important here; in this context it means second in line to the stabilization of your trunk. Secondary stabilization braces the joints of your arms and legs like the primary stabilizers brace your trunk. As you can see from the picture, your quadriceps attach in front so that they can extend your knees with power. Other muscles, like the tensor fascia lata and sartorius, curve around your knee joints. These muscles stabilize and steer your knees so that you can move efficiently. All the joints of your arms and legs have similar muscles to support them.

How to improve quiet balance

If you challenge your proprioceptors and stabilizing muscles in ways that are specific to the functional demands of cross-country skiing, you will steadily improve your ability to balance quietly. Specificity is key; for example, most of us learned to ride a bike and do other balance-intensive activities (such as walking out of the pub) before we learned to cross-country ski. But none of these forerunner activities, all requiring good balance, gave us the knack, the specific balance, to ride a steady ski.

Eight quiet balance exercises are given below. These will:

- increase your sense of balance by fine tuning the proprioceptive signals that guide your

stabilizing muscles,

- build a firm trunk by strengthening your primary stabilizers,

- strengthen your secondary stabilizers to give you more stable, secure joint support.

Developing quiet balance is an easy process but it does require patience. If you try too hard, you'll invariably get it wrong. It's not possible, either, to rush results. You can train balance as often as you want but don't try too hard. If you struggle in workouts, quiet turns noisy because your head is too busy and your body too tight to learn. Make it fun and easy, and aim for three workouts a week. There's no risk from doing quiet balance exercises and the benefits are disproportionately large compared to the small amount of time and effort that you expend on each session. Quiet balance improvement is a continuous process but needs constant training; it can't be dropped after just several weeks of training it. So it needs to be considered as a long-term part of your overall training programme in continuous technical improvement. The following recommendations will ensure that your workouts produce the best results possible:

- progressively explore every exercise: learn the basics: posture, movements, pacing, then try small adjustments and variations. Discover how you

balance best in each case;

- do a set before, during or after endurance training, or in any other combination you'd like;

- gradually reduce the number and size of your balance corrections, including the small movements in your feet;

- don't use your arms to help you balance; it will reduce the overload on your primary and secondary stabilizers;

- maintain firm abdominal tension. Doing the exercise with firm abdominal muscles will substantially increase spinal stabilization;

- close your eyes if you want more challenge, and do the exercise bare-footed;

- do the exercises in sequence. The eight exercises are arranged in a circuit and should be done in the order they're presented.

Exercise 1: Sweet spot

Stand on one leg with you arms hanging at your sides. Look forward, not down. As you balance, gradually reduce the movements of your stance leg and foot. Balance as quietly as you can for 20-30 seconds on each leg. Do all three positions: high, mid and low. For more challenge, scan left and right with your eyes open. Once you're confident with this, try balancing quietly with your eyes closed. For the ultimate balance-sensing challenge, try to balance quietly with you eyes closed while you move your arms around.

Exercise 2: Heel-toe rock

With your feet hip-width apart, rise up onto your toes and hold for a second or two. Slowly lower your heels to the floor and immediately rock back on your heels, lifting your toes as high as you can while maintaining balance. Lower your toes and repeat this cycle 5-10 times. The key to this exercise is achieving balance control through all phases of the exercise. Once you've established this control, try the exercise with your eyes closed.

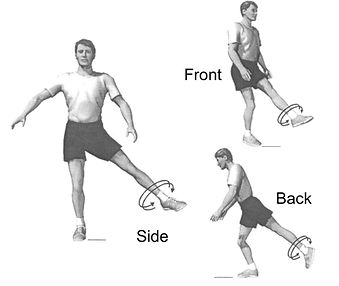

Exercise 3: Hip circles

Balanced on one leg, circle your extended, free leg making circles with your hip muscles. Try to balance as economically and quietly as you can on your stance leg. Do all three positions, alternating legs. Do 5-10 circles per position. Try pulsing your stance leg doing short mini-squats while you circle your other leg. For variation, do the three positions with your hands clasped behind your back.

Exercise 4: T-pose

Balanced on one leg, rotate your trunk and free leg until they're parallel to the floor. If you need help with balance, lean against a wall or a chair. Quietly balance in this position for 2-3 breaths then switch stance legs and repeat. Do 3-5 repetitions per leg, alternating legs. If you want more challenge once you've mastered the basics, try slow quarter squats with your hands behind your back.

Exercise 5: Poser squats

Standing on one leg in a skate-like stance, make shallow, quarter squats while maintaining quiet balance. It is important to look forward, not down at the ground or your feet. Do 12-15 repetitions then switch legs and repeat. Build your rep. count up to 25+ per leg. Also try varying the position of your free leg so that it's forward of your body for several reps, then more behind your body. Once you're feeling comfortable, see how many repetitions you can do with your eyes closed.

Exercise 6: Tick-tock

Stand with your feet located outside your shoulders and with your weight evenly distributed. Tilt your body over onto one leg by pushing off the floor with your foot while you maintain the same foot-to-foot distance. After quietly balancing for one breath cycle on one leg, return to neutral and push off to the other leg and balance quietly. Repeat this pattern 5-10 times in each direction.

Exercise 7: Trunk and hips

In the raised position of a standard push-up, lift your right leg with your hips and hold for one breath cycle, then slowly lower it back to the start position and repeat with the left hip. Do 6-8 repetitions per hip, alternating legs. For variation, start by lowering yourself into a quarter push-up then, as you push up, simultaneously lift your right leg.

Exercise 8: Trunk rotation

Place your feet on a wall with your thighs vertical to the floor. With your hands clasped lightly behind your head and without help from your arms, lift your shoulders off the floor and rotate to the left, then return to the floor by reversing this action. Then with only a light touch-and-go, lift your shoulders off the floor and rotate to the right. Keep up a smooth, continuous motion, moving left and right, touching the floor lightly between rotations. Do 10-15 repetitions to start (left-right counts one), building to 30+ repetitions.